王道銀行教育基金會

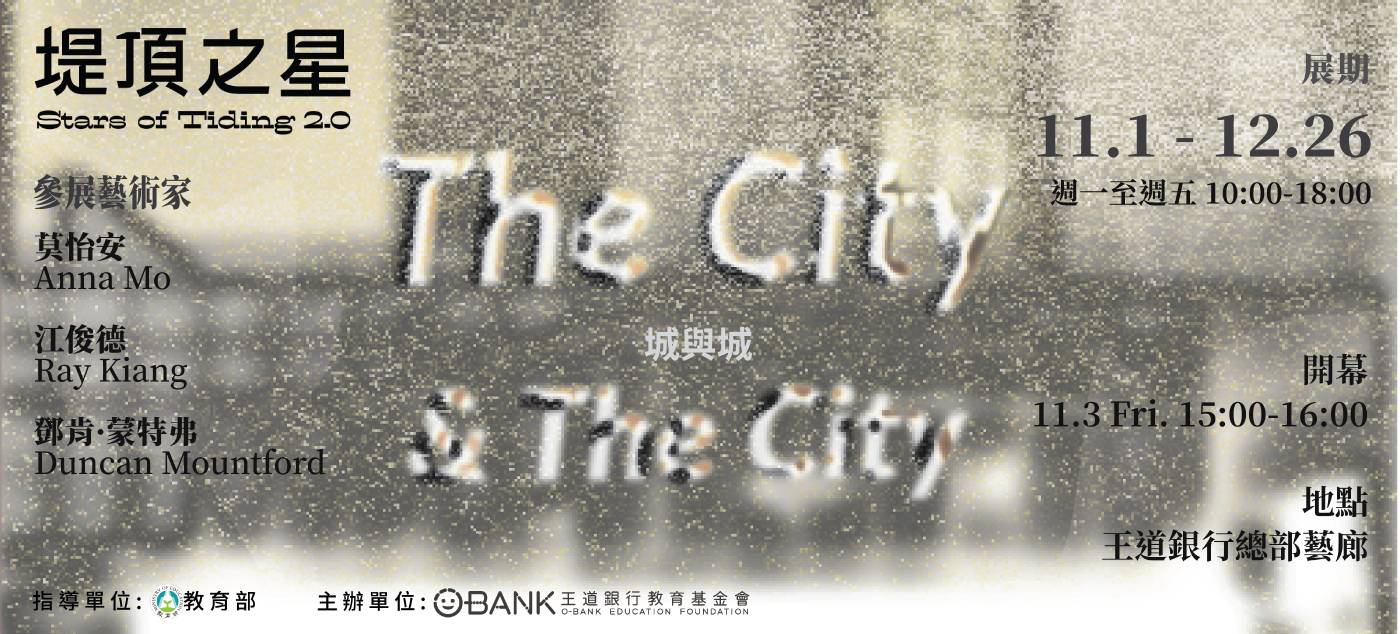

【The City & The City 城與城】2023堤頂之星2.0年度入選展

-

展期

日期:2023-11-01 ~ 2023-12-26

-

地點

王道銀行總部藝廊

-

相關連結

-

參展藝術家

Anna Mo 莫怡安、Duncan Mountford 鄧肯・蒙特弗、Ray Kiang 江俊德

-

人們日常中親身經歷的地方,永遠無法被抽象的地圖完整描述。現今手機和汽車裝備內建的導航系統雖看似精緻,其實並不符合城市生活的核心精神。這些系統(有時確實成功地)指引人們從此地抵達彼方,卻不容許兩點之間的旅程有更多意義。

它們無法真正參與一座城市的發生,所以漫遊城市時使用谷歌地圖總是不大令人滿意的經驗。我們或許確實抵達了咖啡廳,卻似乎錯過了更多——消失建築的殘片、對鷺鳥的瞥眼,以及為了確保汽車順暢通行而無止境修繕重改的周遭景觀。

記憶中的城市由各種經驗、回憶、夢想、慾望、恐懼搭建而成,而你我真正熟悉的城市深繫著潛意識,無止境流變而無法精準製圖。

「在下個記憶左轉,接著在兩百公尺處,讓夢吞噬你。」

英國作家柴納‧米耶維(China Miéville)的同名小說《城與城》,描述了擁有相異語言、政治制度、建築和歷史的兩座城市,它們佔據了同一個地理空間,因此居民必須學會「無視」另一座城市。[1]

城市作為一概念,是透過個人視覺顯化搭建出來的實際空間,居民擁有屬於自己版本的記憶和歷史。所有關於城市街景的見解與想像,源自「我」個人經歷、所屬文化、教育和年代背景,而注定與眾不同;在同樣的物理條件下,我們持有各自的認知。反過來說,物質依據我們的精神而變質。

情境主義理論家紀‧德博(Guy DeBord)提出的心理地理學將城市視為一個超越有形基礎設施架構的場所,與超現實主義以城市作為偶然相遇點的概念相似,但兩者不同之處在於,前者重於城市政治上的解讀,後者視城市為幻境的場域。在英國,這樣的核心概念常被使用在當代創作中,例如電影製片人派崔克‧凱勒(Patrick Keiller)和作家伊恩‧辛克萊爾(Iain Sinclair)等人之作。[2]關於城市作為超越純粹地理條件的概念場域,其歷史可追溯至十九世紀前。[3]從德昆西(Thomas De Quincy)的鴉片夢中城,到布萊克(William Blake)在佩卡姆區一棵樹上遇到的天使,說明了倫敦的豐富背景為城市的概念提供了多重意義。[4]阿克洛依德(Peter Ackroyd)所著的布萊克傳記裡提到,對具有先見之明的詩人來說,城市的意義可是非凡的。

「布萊克所看到的城市,並不如歷史學家想象中的昏暗且骯髒,而是一個充滿天使和先知的地方。」[5]

波特萊爾(Baudelaire)則是在巴黎夜間漫遊時,在相遇的人們身上拾獲了複數現實的可能。[6]每座城市在其居民心中都佔有一席之地。

《城與城》集結了藝術團體 Empty Arts Collective (江俊德、莫怡安、鄧肯‧蒙特弗)的創作計畫。展覽中的城市觀取自藝術家成員各自的文化、地理視角(需要說明的是,在此討論的城市不一定是台北,可能是一個不同版本的台北,一個精神共享卻擁有完全不同形態的地方)。或許這同時是心理地理學(psychogeography)亦是心理地質學(psycho-geology),因為構建我們城市經驗的正是那些記憶和身份的堆疊,唯有在挖掘作品的過程中逐步展露。

展出作品根據藝術家的城市經驗,進一步探索城市如何與記憶和身份相牽連。儘管記憶連結身份的概念司空見慣,城市在此被視為一座記憶劇院,挑選的場景可能直接指涉特定記憶,卻更多促使開展相關經驗的推想。Empty Art Collective 在發展概念的過程中積極互動、研究討論,《城與城》同時展現藝術家在各自領域實踐的成果,以及團隊間的互助合作。

展覽中,一件整體裝置統合涵括攝影、裝置、雕塑形式的當代藝術實踐,每一位藝術家同時使用整體空間進行創作,而非獨自佔據一處所劃分到的空間。複數的概念在此,使得每件獨立的作品得以被放置於另一件作品的脈絡下被看待,呼應了前述城市經驗,即城市的任意局部始終牽繫著那些相異脈絡的他方、他者的記憶。

展覽《城與城》回歸同一座物理城市裡,以不同視角捕捉到的精神景觀,如同小說中的貝歇爾和烏廓瑪城的存在。

江俊德(Ray Kiang)著眼在日常中無所不在的便利商店,將之視為當代資本主義的燈塔,解讀其政治和社會意涵。

攝影作品使用了中型相機,深夜拍攝時,提供庇護和溫飽的商店籠罩在白熾燈的誘惑下,等待換取消費者認可。同時,建築的結構形式揭示了政治、經濟以及個人選擇間的關係。作品重點其實並非便利商店本身,而是意圖利用攝影媒介探討新自由主義的資本主義體系下,選擇局限性的問題。

同時作品攸關當地老店的記憶,如今成為便利商店背後飄蕩的幽魂,經歷了城市的變容、在地文化的興衰,而終將被毫無個性的全球品牌吞噬黯然。

莫怡安(Anna Mo)作品聚焦在城市的邊緣土地。出生於俄羅斯的西伯利亞地區的德國家庭,同時擁有俄羅斯和德國血統的她,將自身對家此一概念的疏離感,投射在對城市邊緣土地的關注上。[7]

介於自然和城市環境間的邊緣土地,交疊著城市與自然的混雜特徵,這些禁區大多是繪製地圖時會被忽略的「無人之地」,隱藏在種種城鄉監控的縫隙間,是通勤者乘坐汽車或火車時不經意著眼,但從未仔細檢視的模糊佈景。邊緣土地的界限屬性隨著個人對城市的了解和界定而異。在我們看來半廢棄的地方,在他人眼裡卻是他們工作或埋藏記憶的地方。

莫怡安展出的三件雕塑參考從前巡迴演出者作背包使用的旅行箱。箱子的原型可追溯自以「Mondo Nuovo」(義大利語:新世界)命名的行動光學箱,這些觀看裝置有各種尺寸和形狀,常配有裝飾性的開口。它們出現在十八世紀初的歐洲,用以娛樂好奇的城市大眾,當時這些箱子奇觀式地播放陌生的全景影像,帶給人們前所未知的他方景象。每個箱子雕塑都搭配一段表演影像,透過反光和透鏡的設計放映給觀眾,藉此互動觀眾猶如沈浸在邊緣境地的全景視覺之中。

鄧肯‧蒙特弗(Duncan Mountford)作品同樣為觀眾創造獨特的觀展情境,進一步促成觀眾與作品的互動。其中一件裝置位於畫廊通往音樂廳的樓梯下方空間,透過門上的窗口能撇見未知空間,雷同的機制同樣可見於畫廊另一端的兩組櫃子。

微型室內的廢墟,不帶解釋也無文本對照。這些場景的一切詮釋,將來自觀眾個人觀點、經驗和知識。由凝視窗口展開的旅程,不需借助機器聲的指引,僅需依靠記憶與想像力來導航。這些空間配有等比例縮小的門,影射那些童年故事中通往神秘世界的秘密入口,乍看之下一切再平凡不過。

城市是一系列持續變動中的情境,對於警覺的城市漫遊者來說,徘徊其中的經驗必包括:曾經的建築、街道、工作場所,被遺忘的紀念碑、忽視的雕塑,痕跡如同往事的鑰匙,將城市化作記憶劇院。

城市作為超越單純物質實體的場所,是個打斷日常慣性、疊合多重遭遇的地方,於此奇蹟或者批判顯身。我們都該拋下那些官方地圖,踏入城市環境中活生生的故事,感受個體經歷對於一座城市的重要性。

[1] Miéville, C., 2011. The City & The City. Pan, London.

[2] 派崔克‧凱勒(Patrick Keiller)的一系列文章可見 Keiller, P. 2013. The View from the Train. Verso, London. 伊恩‧辛克萊爾(Iain Sinclair)寫了許多關於漫遊倫敦的書籍,並揭示了這座城市發展背後不為人知的歷史(及成本),一個例子是 Sinclair, I. 2022. London Orbital.

[3] Benjamin, W., 1999. Selected Writings Volume 2. Belknap Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Mass., London. Bruno, G., 2002. Atlas of Emotions. Verso, London

[4] De Quincey, T. The Works of Thomas De Quincey. 1 Confessions of an English Opium Eater. 1902. Grant Richards, London

[5] Ackroyd, P. 1996. Blake. Minerva, London.

[6] Solnit, R. 2001. Wanderlust. A History of Walking. Verso, London

[7] Farley, P., Symmons Roberts, M., 2012. Edgelands. Verso, London.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Our connection with the places we navigate each day goes beyond the abstraction of the map. For all their seeming sophistication, the multiplicity of navigation aids that now inhabit our phones and cars have no real connection to the experience of place that lies at the heart of living and working in a city. Such systems tell us (hopefully) how to get from this place to that place, but there is no allowance for the journey itself having any meaning other than that of the line between two points.

Such systems do not allow for true engagement with the city, which is why relying on Google maps when wandering a city is an unsatisfactory experience. You may indeed arrive at the coffee shop, but you will miss so much on the journey – the fragments of lost buildings, the glimpse of the heron, the changes being made to the built environment that make the city a place suitable only for cars.

The city that exists in our memory is a place built from experiences, from memories and dreams, from desires and fears. The city we truly know is one that connects to our subconscious, it is a place that cannot be mapped precisely, for it is in constant flux.

“At the next memory, turn left, and in 200 metres allow dreams to overtake you.”

In The City &The City, a novel by the UK writer China Miéville, there are two cities, Beszel and Ul Qoma, cities with different languages, political systems, architecture, histories; yet these cities exist in the same physical space, so that the inhabitants of one city must learn to ‘not see’ the other city[1].

In this we can see a reflection of the idea of the city as a place built from personal vision, with the inhabitants of the cities existing in their different versions of memories and histories. My view of a street stems from my experience, from my cultural, educational, and generational background, and this will be different from yours. The physical space, the architecture and geography, remains the same, but our cognition differs. There is a transubstantiation of the physical coming from our psyche.

This idea of the city as a place the meaning of which comes from factors beyond the physical infrastructure was termed psychogeography by Guy DeBord of the Situationists, and he was reflecting a similar idea of the city as a site of chance encounters to be found in the works of the Surrealists. There was a difference of emphasis, with Situationists focussing on a political reading of the city, while the Surrealists held to the city as a site of oneiric revery.

In the UK such ideas have been central to the contemporary writings and films of, among others, Patrick Keiller and Iain Sinclair[2]. However, as is the case with the Surrealist and the Situationist in Paris, this concept of the city as a place beyond mere geography has a history reaching back beyond the nineteenth century[3]. From the opium dreamt city of Thomas De Quincy to William Blake encountering angels in a tree in Peckham, London has provided the rich backdrop for the city as a site of multiple meanings[4]. In his biography of William Blake, Peter Ackroyd sums up how a city can have entirely different meanings for a poet with a visionary outlook.

“What Blake saw was not the crepuscular and dirty city of the historian’s imagination, but a city filled with angels and prophets.” [5]

For Baudelaire it was the people he encountered during nocturnal wanders in Paris who provided the sense of other realities[6]. For every city is a place unique in the mind and memory of its inhabitants.

The exhibition The City and The City brings together the individual projects of the members of Empty Arts Collective (Ray Kiang, Anna Mo, Duncan Mountford).

The views of the city (and here it should be stated that the city in question is not necessarily Taipei, or it may be a version of Taipei that exists in the same mental space as an entirely different city) in this exhibition stem from the differing perspectives, cultural and geographic, of the artists. Maybe this is psycho-geology as much as psychogeography, for the strata of memories and identities that make up our experience of any city are uncovered in the mining for artworks.

These works are based on the artists’ experience of cities, and on how cities are connected to memory and thereby to identity. The idea of the connection between memory and identity is commonplace, and the city can be seen to function as a memory theatre, with specific places not only allowing access to directly connected memories, but also to further speculations that connect tangentially to the primary direct experience.

When working as Empty Art Collective, Ray Kiang, Anna Mo, and Duncan Mountford develop concepts and work through intensive discussion and research. At the same time they are working on their own projects, and these also form the basis for discussion and collaborative assistance. In The City and The City Empty Art Collective bring together their works in an installation that focuses on the dialogue within and between their artistic practices.

The exhibition covers the range of contemporary art practice from photography to installation to sculpture, and in the installation the works are placed to produce a dialogue between the individual concepts, with each artist using the whole space rather than being sited in a defined area. This produces a multiplicity of concepts, as individual works are seen in the context of other works, in the way in which the experience and memory of any part of a city is never divorced from the context of other places, other memories. There is also a reflection of the dialogue with the work of colleagues and peers that is at the heart of any artistic practice, as all artworks are sited in the space of conceptual dialogue, though some may be hidden down a side alley from the main thoroughfare. The exhibition also returns to the idea of different views of the city inhabiting the same physical space while existing in different psychic landscapes, as with the cities of Beszel and Ul Qoma.

For Ray Kiang the focus is on the ever-present convenience store and the political and social readings of these illuminated beacons of contemporary capitalism.

The photographs of the stores are all taken at the dead of night with a medium format camera, visually enhancing the allure of the incandescent light that provides shelter and food in return for consumer approval, with the dialogue between the different forms of architecture surrounding the stores revealing the connections between politics, economy, and personal choice. The work is not directly about convenience stores, but uses the mediation of photography to open up questions concerning the limitations of choice underlying the neo-liberal capitalist system.

Memory is here as well, the memory of the old local shop as a ghost behind the facade, fading as the face of the city shifts identity from an individual local culture to that of a global brand.

In the work of Anna Mo it is the edgelands of cities that are the focus. Anna Mo was born in the Siberian region in Russia to a family originally hailing from Germany. With this Russian and German ethnicity, she can feel disconnected from the idea of home, and this is reflected in her interest in the edgelands of cities[7].

Edgelands exist in the zone between natural and urban environments, and, within these liminal zones, the distinctions between city and nature intertwine. Edgelands are mostly unmapped “no-man’s land”, between the watched and documented territories of urban and rural. They are places of passing, looked at while we are in a car or a train, but not closely examined, serving as a blurred backdrop for the commuter. Definitions of the liminal property of edgelands shift with the individual’s knowledge of the identity of the city, what one sees as a semi-abandoned location, is, to others, the place where they work or where their memories are buried.

Anna Mo exhibits three sculptures based on historical traveling boxes designed to be carried as a backpack by iterant showmen. This idea behind these boxes can be traced back to the traveling optical boxes named in Italian “Mondo Nuovo” (meaning “new world”). These were viewing boxes of variable size and shape, often decorated with openings. They began to appear in Europe in the early 18th century to entertain the curious public of the big cities with panoramic views of cities or previously unseen sites or cultures, depicted in spectacular ways.

Each box sculpture contains a screen showing a video of a performance, installed so that the video is seen via mirrors and lenses. The interaction with the box this produces allows the viewer to become absorbed in the panorama of the edgelands.

Duncan Mountford’s works also produce situations where the viewer has an active engagement with the process of seeing the work.

One of his works is installed in the space beneath the stairs that leads from the gallery to the concert hall. Here a window in a door allows a glimpse into an unknown interior, and this accessing of strange spaces via windows is replicated in the two cabinets that are installed at either end of the gallery.

The miniature interiors of the works are sites of ruination that provide no simple narrative of meaning or history. Interpretation is a function of personal perspective, and so the stories that can be woven around such sites come from the viewer. The interiors glimpsed through the windows are navigated with the assistance of memory and imagination, not the voice of the machine. The viewer therefore draws upon personal experience and knowledge to construct narratives concerning the spaces. The installation of the spaces, with scaled-down doors, references childhood stories of mysterious doors to hidden realms, though in this case the realm is quotidian at first glance.

Cities are ever-changing environments, and any wandering of a city will always discover, to the alert flaneur, the traces of previous buildings, streets, workplaces, forgotten monuments and ignored sculptures. These function like the keys to memories and stories, turning the city into a memory theatre.

The works in the exhibition draw on the city as a site beyond the mere physical, as a place that contains multiple encounters that can disrupt the everyday and allow the marvellous and the critical to appear. Ignore the official maps and recognise the multiple perceptions and stories that make up any urban environment, and recognise the importance of personal perceptions of the environment of the city.

[1] Miéville, C., 2011. The City & The City. Pan, London.

[2] A series of essays by Patrick Keiller can be found in Keiller, P. 2013. The View from the Train. Verso, London. Iain Sinclair has written many books based on wandering London and uncovering the hidden histories (and costs) of the development of the city. An example is Sinclair, I. ???? London Orbital

[3] Benjamin, W., 1999. Selected Writings Volume 2. Belknap Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Mass., London. Bruno, G., 2002. Atlas of Emotions. Verso, London

[4] De Quincey, T. The Works of Thomas De Quincey. 1 Confessions of an English Opium Eater. 1902. Grant Richards, London

[5] Ackroyd, P. 1996. Blake. Minerva, London.

[6] Solnit, R. 2001. Wanderlust. A History of Walking. Verso, London

[7] Farley, P., Symmons Roberts, M., 2012. Edgelands. Verso, -

REFERENCE

推薦展覽

view all王道銀行教育基金會

【消逝的記憶地圖 The Atlas of Disappearing Memories】2023堤頂之星2.0年度入選展

日期:2024-01-26 ~ 2024-04-03|台灣,台北市